Two apologies:

First of all, sorry about sending an email with a picture of severed heads last week. I realized, after I sent it, that it was in fact the second newsletter I had sent featuring severed heads in the short lifespan of this newsletter. It seems I have discovered a previously unsuspected interest. Still, I was amazed that I had never come across the picture. From the responses on Instagram, it seems the picture was well-known in Brazil—as it could hardly fail to be. The bandits Maria Bonita and Lampião, the Bonnie and Clyde of the sertão, are one of the most mythologized pairs in Brazilian history: so legendary that I suspect that many Brazilians today don’t realize that they were real people.

My friend Luciana sent me a text by Graciliano Ramos that dates from the moment in 1938 when Lampião and his band were captured and killed. Graciliano was from the same state, Alagoas, that was the home of Lampião. It’s a state with a long history of resistance, most notably in the colonial period, when escaped slaves and Indians formed the Republic of Palmares, the best-known of the quilombos. It was also the state where, in 1922, the infant Clarice Lispector disembarked in Brazil.

Like so many other interesting things, Graciliano’s essay doesn’t seem to be online, and it doesn’t seem to be translated. So I’ve remedied that here. First in English; embaixo em português.

For those interested in Graciliano Ramos, his novel São Bernardo has recently been translated into English by Padma Viswanathan at the New York Review Classics. I haven’t read this translation, but he is an excellent writer, as I hope you’ll see from the piece below.

My second apology follows.

Heads

When, a while back, Lieutenant Bezerra finished off Lampião and came triumphantly to Maceió leading a fine collection of heads, the backwoods folk of Sant’ana do Ipanema greeted him with festivities—and the hero made a speech. The papers didn’t publish this oration, which was reported in telegrams. We know, however, that the valiant official declared the bandit definitively dead, an imprudent miscalculation that shouldn’t have been broadcast.

We see here a sign of a mixup—of a reigning confusion, a confusion that the press senselessly aggravates.

A few days ago, a journalist friend interviewed a certain girl who had suddenly become well known—because of a beauty contest, I believe. He chatted with her for half an hour and, having asked several quite indiscreet questions, inquired about her thoughts on literature. Taken by surprise, the little lady spoke without enthusiasm of Escrava Isaura, but saw in the magazine that her answer had been enhanced by a list of unknown novels, which she naturally bought and read, itching and yawning, in order to arm herself against a new assault.

Thus are many reputations organized.

Far be it from me to censure my journalist friend and the population of Sant’ana do Ipanema, which cheered the lieutenant. The reporter didn’t have any reason to judge the pageant girl ignorant of letters, though it would have been more reasonable to ask her about face powder, cream, rouge, and other ingredients necessary to beauty.

Neither should we assume that Lieutenant Bezerra can’t cook up a decent speech. He might even be an excellent orator: he’s good looking, has a pleasant voice, and his smile flashes a gold tooth that embellishes his mouth. With these qualities, he could have practiced giving patriotic rants to his fellow soldiers in their free time in the barracks. It’s reasonable, however, to fear that the valiant officer wasn’t a specialist in this area, and that his harangue was a failure. From the news that reached us here, we know that Lieutenant Bezerra is handy with a machine gun and skilled in the art of cutting off heads, things which are actually quite hard to do. In Alagoas, as in other places, there are lots of chatty men who talk for hours without saying a thing, but none of them would venture into the backlands and set up ambushes with the assistance of the same local people who help out the bandits, a dangerous business; none of them ever aspired to the honor of decapitating his fellow man. So why did the brave officer of public order expend his energy in an unequal competition, when the best thing would have been to dedicate himself wholly to his profession? Maybe Lieutenant Bezerra still has a lot more heads to hack off, which will be carefully measured, like the eleven of the first series. His prestige will grow, Lieutenant Bezerra’s; already big, it will become enormous.

The speech is the thing that’s a bit off: we notice in it a kind of justification, the same way we see something a bit off in the girl’s literary notions.

A few demanding readers might think the beauty pageant was silly. But the journalist works it all out: pretending to talk to the woman and slyly insinuating that she’s become interesting—not only because of her lovely eyes and well-turned legs, but because she’s familiar with the novels of Mr. Lins do Rego. This satisfies the public—a very reduced part of the public.

On the other hand, there are people who are too sensitive and who shiver at the sight of photographs of heads outside of bodies. These people need an explanation. Cutting off heads isn’t always barbarous. Cutting them off in the middle of Africa, and without a speech, is barbarous, of course; but in Europe, with an axe and with a speech, isn’t barbarous. The speech brings us closer to Germany. Of course, we still have a ways to go, but we are making progress, we’re not barbarians, thank God.

Cabeças

Quando, há algum tempo, o tenente Bezerra deu cabo de Lampião e se dirigiu triunfante a Maceió, conduzindo uma bela coleção de cabeças, os sertanejos de Sant’ana do Ipanema receberam-no com festas—e o herói fez um discurso. Os jornais não publicaram essa oração noticiada nos telegramas; sabemos, porém, que o bravo oficial declarou o cangaço definitivamente morto, juízo imprudente que não devia ser transmitido.

Temos aí um sinal de trapalhada, da confusão reinante, confusão que a imprensa agrava de maneira insensata.

Um jornalista meu amigo foi há dias entrevistar certa moça que de um momento para outro se havia tornado notável, em consequência de um concurso de beleza, creio eu. Palestrou com ela meia hora e, feitas várias perguntas bastante indiscretas, pediu-lhe que se manifestasse a respeito de literatura. Pegada de surpresa, a mulherzinha falou sem entusiasmo da Escrava Isaura mas viu numa revista a sua resposta aumentada com uma lista de romances desconhecidos, que naturalmente comprou depois e leu, cochilando e bocejando, para se armar contra novo assalto.

Desse modo se organizam muitas reputações.

Longe de mim a ideia de censurar o meu amigo jornalista e a população de Sant’ana do Ipanema, que aclamou o tenente. O repórter não tinha motivo para julgar a moça do concurso ignorante de letras, embora fosse mais razoável interrogá-la sobre pó de arroz, creme, rouge e outros ingredientes necessários à beleza.

Também não podemos considerar o tenente Bezerra incapaz de improvisar discursos decentes. É possível até que ele seja um ótimo orador: tem boa figura, voz agradável, e sorri mostrando um dente de ouro que lhe enfeita a boca. Com essas qualidades ele pode ter-se exercitado em deitar falações patrióticas aos camaradas nas horas que lhe deixaram os trabalhos da caserna. É lícito, porém, recearmos que o valente oficial não se tenha especializado nisso e que a sua arenga haja falhado. Pelas notícias aqui recebidas, sabemos que o tenente Bezerra maneja com proficiência a metralhadora e é perito na arte de cortar cabeças, coisas na verdade bem difíceis. Em Alagoas, como em outros lugares, há uma quantidade regular de homens loquazes que falam horas sem dizer nada, mas nenhum deles se aventura a mergulhar no sertão e armar emboscadas com o auxílio de coiteiros, negócio perigoso; nenhum aspirou à honra de decapitar o próximo. Por que então o brioso agente da ordem gasta energia numa concorrência desleal, quando melhor seria dedicar-se inteiramente à sua profissão? Talvez o tenente Bezerra ainda precise cortar muitas cabeças, que serão medidas cuidadosamente, como as onze da primeira série. O seu prestígio crescerá, o tenente Bezerra, que já é grande, ficará enorme.

O discurso é que destoa: enxergamos nele uma espécie de justificação, como nos conceitos literários da moça.

Na opinião de alguns leitores exigentes, o concurso de beleza era uma tolice. Mas o jornalista arranja tudo: finge conversar com a mulher e habilmente nos insinua que ela se tornou interessante, não apenas por ter belos olhos e pernas bem-feitas, mas por conhecer os romances do sr. Lins do Rego. É uma satisfação ao público, a uma parte muito reduzida do público.

Por outro lado, existem pessoas demasiado sensíveis que estremecem vendo a fotografia de cabeças fora dos corpos. Essas pessoas necessitam uma explicação. Cortar cabeças nem sempre é barbaridade. Cortá-las no interior da África, sem discurso, é barbaridade, naturalmente; mas na Europa, a machado e com discurso, não é barbaridade. O discurso nos aproxima da Alemanha. Claro que ainda precisamos andar um pouco para chegar lá, mas vamos progredindo, não somos bárbaros, graças a Deus.

— de Cangaços, Graciliano Ramos (Record, 2014)

Now comes the second apology.

I am always struggling not to make this newsletter, which after all has a Brazilian name, entirely about Brazil. But it’s a fact that I have been engaged in one way or another with Brazil and Brazilians for most of my life, and that I have always read a lot of Brazilian books.

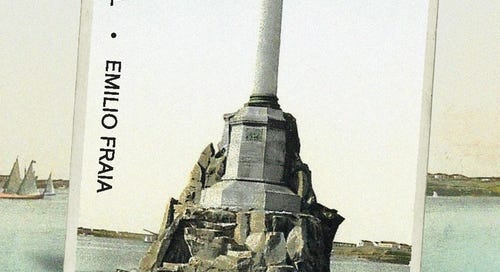

I’m excited to announce that New Directions, where I’ve been publishing the works of Clarice Lispector for all these years, has just published Sevastopol by Emilio Fraia. If Graciliano Ramos describes the old, romantic Brazil of a century ago, Emilio Fraia describes something much more like the country that exists today—the country and people I know: people who resemble Lampião and Lieutenant Bezerra far less than they resemble middle-class people anywhere else.

It’s a weird book: three connected stories loosely based on the Sebastopol Stories of Tolstoy. It’s weird because the stories are connected—but how, exactly? And it’s weird because the stories themselves are constantly wrong-footing you. You think you know what’s happening, and then suddenly you realize you don’t. I read the book twice—once when it came out in Portuguese, a few years ago, and once more when I got this new translation, by Zoe Perry. (The translation is excellent, by the way.) I thought I understood it the first time. The second time, I was sure I didn’t. That’s why, though it’s a short book, it’s been bouncing around in my head these last few weeks, and why I’m thinking about reading it one more time.

To give you a taste: one of the stories was published in The New Yorker a couple of years ago, and Fraia has just published something new in The Paris Review, related, kind of, to another one of my favorites, the Uruguayan writer Juan Carlos Onetti.

Speaking of Brazilian books abroad: I am proud to be speaking about Clarice Lispector in Bulgaria—which these days is a more exotic way of saying “in my kitchen”—alongside Jeffrey Eugenides and Dimiter Kenarov, who are also talking about writers who influenced them. It’s part of the ongoing work of the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation, who have done so much to bring international literature to Bulgaria and to bring Bulgarian literature to international readers. You can’t really tell from this graphic, but this is happening tomorrow. Click below to register.

Benjamin Moser on Clarice Lispector

Moderated by Nadezhda Moskovska

Free I Online

23 June ::: Wednesday

12:00 PM EST (New York), 7 PM EEST (Sofia)

Duration: 60 min

In English

Finally—and not about Brazil—I will be speaking on Sunday to Daniel Oppenheimer about Far From Respectable: Dave Hickey and His Art. I absolutely love this book, the first book-length exploration of one of the strangest and most eccentric of Texans, gallerist-cum-critic-cum-writer-cum-total-fuckup Dave Hickey, who is indeed far from respectable—and who, for that reason, has all of my respect.

Click here to register.

Thanks for reading—and, as always, if you like getting these newsletters, please consider subscribing: it’s a big help to me.

I love getting comments—I feel sort of sad when nobody leaves them!

And if you want to share this to your social media, just give this a click—

Heads, Cabeças. Translation. Right ? Very nice. I have tried to translate fr, colette peignot, bataille's friend. but did it very literal so it comes off choppy. and the language dated to its time of course. what to do about that... k off now. Thangs again the bio!