Today I’m proud to be cross-posting this in the European Review of Books, one of the most hopeful new projects of the last few years. It’s already attracted some great collaborators, including David Mitchell, Ali Smith, Simon Kuper, and Rem Koolhaas. It’s still in its crowdfunding phase. Subscribe if you can; it’s a huge help to a new publication.

I contributed an essay about Brazil to underline something important about the ERB: it’s located in Europe, but it’s not only about Europe: it’s about the whole world of books and ideas.

I left Brazil in December 2019. I hardly imagined how soon it would start to feel more than merely far away: within a few weeks, it would come to feel as if it had come entirely unhinged from the rest of the planet. And now that “we” are emerging from the great unhinging, it still does—though things are slowly improving there too, and though it’s starting to be possible to imagine going back. And in this time I’ve thought about why Brazil has been so central to my life.

It’s hard to say why a country becomes important to you, just as it’s hard to say why some people become important to you and why others—even people you really like—are merely passing through.

One reason Brazil has always interested me is because it’s a place where boundaries are blurred. This might sound abstract. But in practice, it means that things are never what they seem. You’re always being surprised, wrong-footed.

One example: when I’ve translated Brazilian books, I’ve always found that alongside the standard Portuguese grammar, there’s another shadow grammar, a way of expression that is always undermining and playing with the official language. Spelling changes; words move around; the language feels slippery, elastic, full of poetic possibilities. That, for me is typical of Brazil, where every category—down to the grammar of the language—seems open to redefinition.

Except one.

This is the category called “modernism.” And this, as anyone who knows anything about Brazil knows, began in 1922. And not just in that year. On a specific day in that year, February 10, when the “Week of Modern Art” kicked off in São Paulo.

By the end of the week—the story goes—a coterie of rebellious artists had roused an academic, Francophile, hidebound culture from centuries of slumber, marking a continental divide nearly as consequential as the nation’s independence from Portugal a century before.

The two leading figures in the literature of “22,” Oswald de Andrade and Mário de Andrade, had little in common. (Despite sharing a last name, one always has to point out that they were no relation.) Oswald was rich and Mário was working class; Oswald was white and Mário was of mixed race; Oswald was straight and Mário was gay.

Oswald is prankish. Mean, too: always lashing out at some other writer, bitchy in that Deep Straight Guy way. (Admit it, reader: you know the type.) Mário is serious, often to the point of ponderousness. They eventually had a brutal and public falling-out.

What they have in common, besides participating in the beginnings of the “22” project, is that I don’t especially like their books. I have tried and tried, because I have spent so many years reading Brazilian literature, and because they are considered central to that literature. But I find both, in their different ways, tedious. I don’t feel much when I read them.

The contrast with the writers of the previous generation—João do Rio, Lima Barreto, Julia Lopes de Almeida, Benjamim Costallat—is striking. So is the contrast with the writers that emerged in the following decades.

I’ve had to conclude that theirs just isn’t my thing. It’s similar to the way I feel about the architecture of Oscar Niemeyer. You’re told it’s “important.” So you feel guilty for not liking it more.

(A good thing about growing older: you stop feeling guilty, and trust more in your own taste.)

If there’s one thing I love, it’s a good revisionist history. Revisionism, even when wrong, has a hygienic purpose in societies. It protects us from intellectual sclerosis. It forces us to reexamine assumptions that so often crystallize into dogma. It makes us look again.

In Modernity in Black and White: Art and Image, Race and Identity in Brazil, 1890-1945, Rafael Cardoso unravels the myth of 1922 and takes a much broader view of what modernity meant in Brazil.

In it, I understood a lot of my uneasiness with the work of the 1922 writers and artists, and found an advocate for the Brazilian literature and art I’ve always loved.

I discovered Cardoso’s work years ago. He’s the nephew of Lúcio Cardoso, a notable writer of the post-22 generation and Clarice Lispector’s closest friend.

Rafael’s books about Brazilian art history take an unusually generous view of art and history: in this land of blurred categories, the broader perspective is usually the right perspective. He mostly writes in Portuguese, but because he grew up partly in the United States he speaks unaccented English, allowing him to interpret Brazil both for Brazilians and for those from elsewhere.

In Modernity and Black and White, Cardoso takes on a number of “widely held but utterly false” views about modernism. About race, for example. He quotes an American critic who introduced a show of Brazilian art in Detroit in 1940.

The debt that modern Brazilian culture owes to the folklore, the dances, the music, the cult art of the negro was acknowledged by the intellectuals of São Paulo in that Week of Modern Art of 1922 which was the first public recognition of indigenous and regional art in Brazil. Since then a school of startling vigor inspired to a large extent by the negro has grown up. Forswearing the artificial picturesqueness of their francophile predecessors the modern Brazilians have tried to understand the negro and his relationship to themselves, and upon the resulting conceptions they have based their art.

“Nearly every claim in those few sentences is misleading or factually incorrect,” Cardoso writes. And indeed the paragraph is not so remarkable for its incorrectness—it’s easy to dismiss as old, and written by a foreigner—as for the ways that this view has penetrated the views of Brazilians themselves. These claims need to be rebutted precisely because they are so common.

By 1922, Brazilians had already been trying for decades to imagine what a modern version of their country could look like. They had come up with a number of startlingly different views. In this art was nothing less than a debate about what kind of country Brazil wanted to be.

One case is the iconography of the favela, an institution that emerged in Rio de Janeiro in the last years of the nineteenth century, when this book opens.

The word first referred to a single place, a hill called the Morro da Favela where poor migrants and formerly enslaved people settled.

For Brazilian artists, the Favela, later generalized to the favela, was part of the same movement as automobiles, jazz, and futurism: an indication of a modern upheaval artists urgently tried to portray.

Cardoso offers incisive readings of the very first favela images, including of a painting by Eliseu Visconti, A Street in the Favela.

He points out that the painter’s loose brushstrokes blur the woman’s feet, thereby denying the viewer “the crucial information of whether they are bare or shod.” The work dates from 1890, two years after abolition; the question of the feet is crucial because Brazilian slaves were not allowed to wear shoes.

The iconography of the favela was not restricted to “fine artists” like Visconti. I wish I could reproduce all the images in Cardoso’s book. He has a vast knowledge of this material and a flair for fishing shocking, funny, and surprising images out of the archives.

Take this one, “The Favela Insulted.” It features the president of Brazil—a well-suited and -coiffed type of Latin American politician recognizable to this day—visiting the favela.

“I can make lots of improvements here on the hill,” the president says. “But you also need your representative on the city council.”

To which the black man says: “Ah! Sir! That would be degrading Favella Hill even more…”

From the beginning, Cardoso says, the favela was seen in aesthetic rather than social terms. This is one reason its iconography is so fascinating. Its inhabitants were not, for example, always portrayed as black. In the early years, it was shown as inhabited by people of all different races, as in fact it was.

It was precisely the 1922 modernists who racialized the favela, often in terms that were inaccurate as well as embarrassing.

(“The negro is a realist element,” Oswald de Andrade once said—at, of all places, the Sorbonne.)

Oswald’s wife, the painter Tarsila do Amaral—she, like him, hailed from the upper reaches of São Paulo society; their wedding was attended by the same President of Brazil in the caricature above—further emphasized this “realist element.”

These images were mainly produced in Paris. Cardoso shows that they are more closely related to French trends for negrophilia, jazz, and primitivism—to the Josephine Baker of La revue nègre—than to any serious consideration of Afro-Brazilian culture.

What does modern mean? Technically, etymologically, it means something happening now. But in Brazil, it often meant an embrace of newness as the possibility of reinvention. This is a powerful strain in Brazilian culture, and especially at the time that Cardoso writes about here.

In the year his study begins, 1890, we are two years past abolition and one year past the overthrow of the monarch, a descendant of the Kings of Portugal whose family had ruled, as Emperors of Brazil, since independence in 1822.

It was a time when everything stood to be reinvented—a time when Brazilians were extremely open to new ideas.

One question prevailed: what relationship would there be between the official Brazil—the Brazil inherited from the empire, with its palaces and patisseries and avenues—and “deep” or “real” Brazil—the Brazil of the backlands, the enslaved, the urban masses?

This was the encounter symbolized by Favela Hill, a short walk from the grandest promenades of official Rio. It was the encounter that spilled onto the streets in Rio’s increasingly extravagant carnivals. It was the time of the year when traditional boundaries—between classes and races and genders—were blurred, at least temporarily, and at least in theory.

This encounter wasn’t always respectable, according to the mores of the time— including because it was so often sexual. It captured the attention of many artists who lived, or at least aspired to live, in a place outside the mainstream of society.

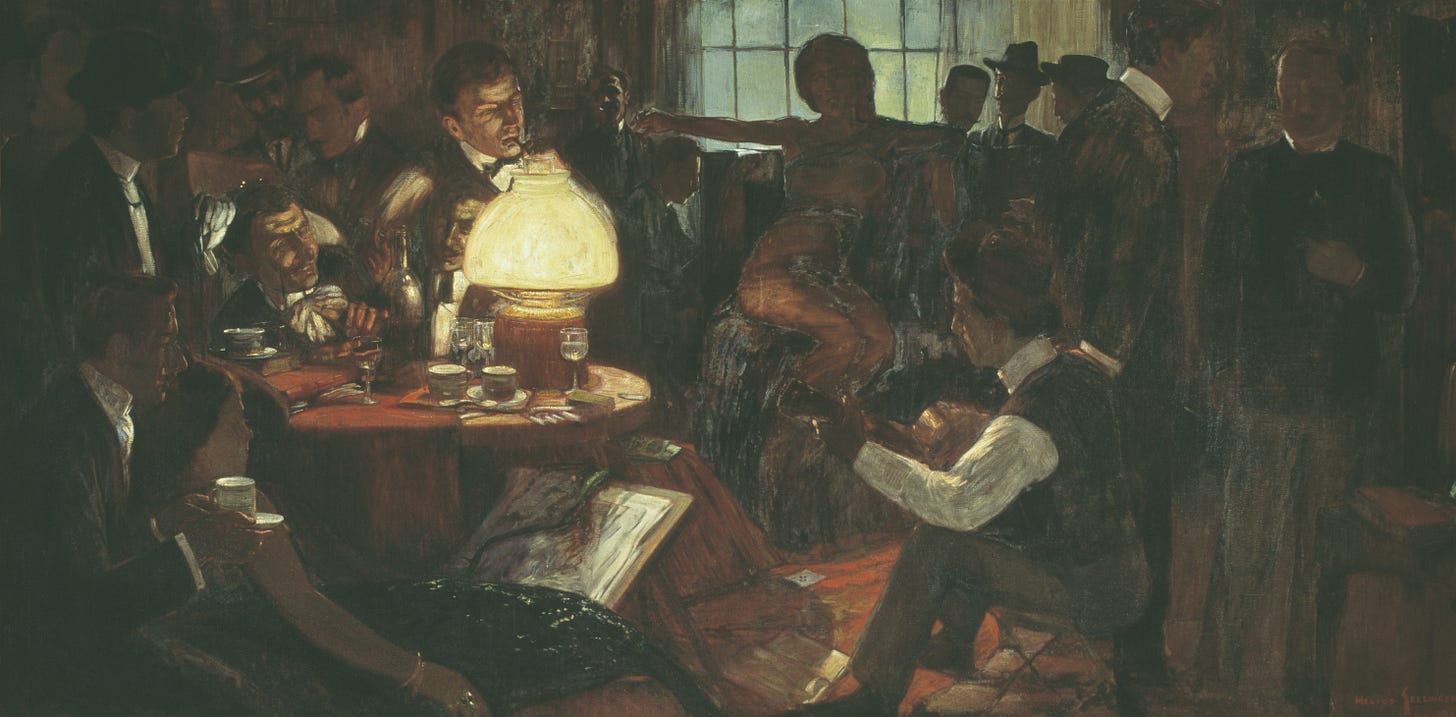

That idealized place was called “Bohemia.” Cardoso offers a detailed interpretation of a painting from 1903 by the now-mostly-forgotten Helios Seelinger. It shows Rio’s leading bohemians. Later caricatured as the representatives of a tragically retrograde “bourgeois” or “academic” culture, they were themselves eccentric in the extreme, trying to create a way of thinking and living that would be genuinely countercultural.

But to say that something is countercultural implies a single dominant culture, and it has always seemed to me that the whole point of Brazil is that such a thing never really existed. The urban middle and upper classes were always too small and too insecure to allow themselves the luxury of ignoring the millions of miles of the rest of the country.

(This uneasy cohabitation in a gigantic and contradictory land is one thing Brazilian literature shares with Russian literature.)

Despite the later idea of this urban culture as aloof from the rest of the country, Cardoso shows how artists and journalists were, in fact, constantly striving to represent and understand it. In a fascinating chapter, he juxtaposes the craze for art nouveau—

—with another quintessentially modern phenomenon, the cult of celebrity. I was astonished to learn that in the 1930s the mythic outlaw Lampião was “arguably the biggest celebrity in Brazil,” and that he managed his reputation carefully. At one point his group “undertook an overhaul of its appearance, introducing a new wardrobe and colorful accessories.” He let himself be filmed for a documentary; he was described as “a movie star.”

You can see this wardrobe and accessories in a picture taken after Lampião and his group were killed in 1938, the climax of a seven-year manhunt. Trigger warning! Cardoso describes this picture as “one of the most infamous images in the visual culture of Brazil,” and I am amazed that I had never seen it before.

It shows the severed heads of Lampião and nine of his companions. Lampião, his face bloodied, is in the bottom row, center.

The barbarity is old. But the carefully composed and photographed display of that barbarity is new. The ways these images interacted, their always uneasy, often violent coexistence in a huge nation, is the subject of this excellent book.

To subscribe to this newsletter, please click here

To leave me a comment, please click here

To share this piece on social media —

Always enjoy what you’ve got to say and how you say it.