A trip to Hebron

The worst place in the world

If you like getting these weekly emails, can I ask you to subscribe? It’s cheap! But it means a lot to me—and the more people who contribute, the better I can make this newsletter. Thank you!

Five years ago this month, I attended the Palestine Festival of Literature, an initiative of the Egyptian writer Ahdaf Souief. She is one of the people I admire the most in this world—a kind woman, a wonderful writer, and someone who has found a way to do something many artists wish we could do, or wish we could do better: make some impact in the “real world,” which is to say: in real people’s lives.

Because here’s the thing. Compared to the real world of banks and armies and governments, your little novel, your evocative sculpture, your lachrymose ballad, will never really feel that important.

It’s true that we do these things because, in a way we can’t quite articulate, we feel that books and paintings and songs are more important than banks or armies or governments: that in some mysterious way, art and ideas move the world. We believe this, but it always feels grandiose, since the results are so hard to see.

I don’t know any writer who has devoted as much of her time and energy to activism as Ahdaf has. At PalFest, international writers—mainly from the English-speaking world—come together with Palestinian and Arab writers. That could happen in Lyon or Berkeley or Milan or, these days, on Zoom. But what’s unique about PalFest is that it shows you the situation. And the situation is very hard to see, even for people who want to.

If you’re Jewish, and even more so if you’re a Jewish American, you always feel a bit dishonest when writing about this subject. Maybe that’s why I never have. Enough people are writing about it, after all. You feel a bit sad for parents and grandparents for whom Zionism was a sacred cause — one that, for many of them, replaced religious feeling, and gave them a sense of connection to something larger than themselves, and for which many of them died.

Before you can start to feel the justice of the Palestinian cause, you have to go through a lot of steps: deprogramming your mind. First, you have to acknowledge that Palestinians actually exist. (This seems like a joke, but it’s not: lots of people I grew up around thought this wasn’t quite clear.) Then you have to acknowledge that they, too, have a right to their own country. Then you have to deplore the violence that has plagued historical Palestine—one which, yes, has plagued both sides, Palestinians and Jews.

But then, year after year, a feeling of nausea grows as you realize—there aren’t really both sides. You feel you have to state that you are aware of the Jewish perspective—as if there were any possibility that you could have been unaware of the Jewish perspective. You have to denounce anti-Semitism, the Holocaust, the attack on a Jewish kindergarten in Toulouse, something crazy some Iranian official tweeted.

But even when you have penetrated this rhetorical fog and are ready to support, mentally and emotionally, the Palestinian cause, it’s hard to see what the occupation actually means.

It’s easy enough to go to Israel—you can even get paid to do this by various propaganda outfits—and feel inspired at Masada, or walk through the magical streets of Jerusalem, or visit the beautiful museums that tell the story of “The Jews in Their Land.”

While you’re there, it’s easy to express your fuzzy hopes for Peace—and leave it at that. Because unless you really want to, it’s pretty easy not to see the Palestinians. And then someone says: Well, don’t you think Israel has a right to exist?—and the fog descends again.

After all, it’s all so complex.

The thing is: it’s not complex. It used to be. It’s a complex story that goes back as far as you want it to go, to 1967 or 1948 or, if you want to, all the way back to the Bible. It’s complex because it’s now probably impossible to solve.

But morally? These days? Not complex. Just spend an afternoon in Hebron.

Hebron is a city whose name—al-Khalil in Arabic and Khevron in Hebrew—means, ironically enough, “friend.” Its main feature is the tomb of Abraham or the Cave of the Patriarchs, a large fortress where people from different faiths have worshipped for centuries.

To get to Hebron, just south of Jerusalem, you have to go through the usual checkpoints. Usual, but only in Palestine: these are huge buildings where you can wait for hour upon hour—even if, like me, you have a “good” passport—i.e. not from a Muslim or other poor country, and certainly not a Palestinian ID card—standing on interminable lines and getting checked out by soldier after snarling soldier.

When you travel in Palestine, you get used to the feeling that short distances, distances of a few kilometers, are vast. It’s incredibly hard to get anywhere, full of unbridgable distances. People in Bethlehem or Ramallah might long for Gaza or Jerusalem as someone exiled to Siberia might long for Paris. And the difficulty of travel is reserved for members of a certain race or ethnic group, which happens to be the same ethnic group that is indigenous to this land. These people use crappy, often unpaved roads—roads that run directly alongside paved freeways that are reserved only to another race.

When you get to Hebron, you disembark in a plaza in front of an ugly building named for an Australian Chabadnik called—you can’t make it up—“Diamond Joe” Gutnick. It looks a bit like a roadside attraction you would find at a gas station in rural Brazil, selling tacky souvenirs and offering buffet lunches to passing truckers. It features listening posts and radio masts shaped like palm trees.

This is the headquarters of the local settler movement, from which you walk a short way into the heart of the old city, the marketplace. Almost all the shops in the marketplace have been shuttered, and heavily armed Israeli soldiers patrol it, bristling with weapons. If you are familiar with the Middle East, you know how busy such marketplaces usually are, how full of life, how heaped with spices—how populated with oversized stuffed animals.

A bit further on are the lodgings of the settlers. These, like Diamond Joe himself, are not from Hebron, and not, for the most part, Israelis: they are, in fact, mainly American. They don’t actually live here—there’s nothing you could really do in Hebron, economically, except maybe attend some fanatic yeshiva. What they are mainly there to do is harass Palestinians. The few surviving shopkeepers have had to cover the open walkways with wire and netting to protect themselves from the garbage, sticks, and tear gas that is constantly thrown on top of them from the settlers in the windows overhead.

When my parents were growing up, Jim Crow was the law of the land in our state. When I read about it as a child, it seemed so bizarre and exotic to me—separate water fountains for black people?—that I am astonished to realize how recently it ended: only a few years before I was born.

Yet Hebron felt worse to me than anything I’d read about Jim Crow. Worse than apartheid—a word that is now, finally, being applied to Palestine. I suppose that, in this day and age, I have to specify that I am not in favor of Jim Crow or apartheid. But all black Americans were citizens of the United States from 1868. The promise of this citizenship was imperfect, and in many ways still is. But it was a legal fact. And there were choices: if things were bad in Mississippi, you could move to Los Angeles. If you couldn’t live in America, you could get a passport, go somewhere else, and come back whenever you wanted. In South Africa, non-whites were around ninety percent of the population. It would have been impossible for the white minority to maintain its supremacy forever.

For me, the point was that these things felt like legacies of the past. You could be horrified by them the way you felt horrified by Nazis: by something, no matter how terrible, that was over.

In Hebron, I saw a racial tyranny that was not only not over: it was actively getting worse. I saw ethnic cleansing happening in real time, house by house, block by block.

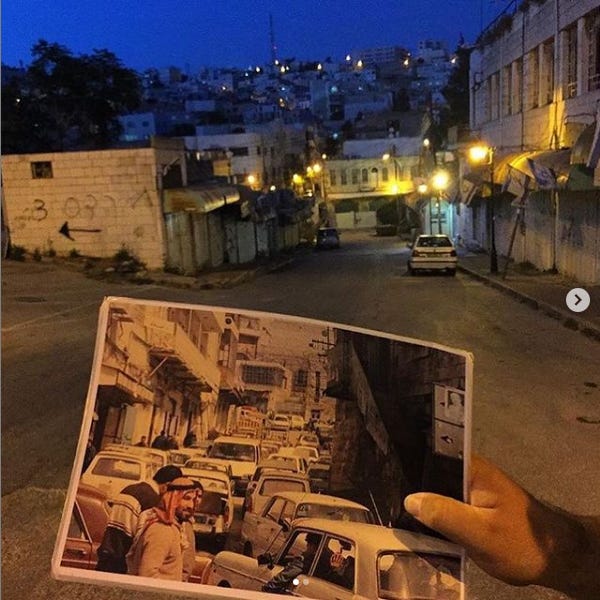

Take this street, a before-and-after photographed by my friend Porochista Khakpour.

This is a street from which people belonging to a certain ethnic group are banned. So I, with my “good” passport, can walk down this street, but people who are from this city, whose families have lived here for centuries, cannot. A busy commercial artery that was now utterly closed and lifeless.

(The people in the photograph below aren’t Palestinians; they are writers who were attending the festival.)

The restrictions on Palestinian life—starting with the simple ability to walk down the street—are so suffocating that you can’t quite believe you’re not in some grotesque movie. The Palestinians have no citizenship, and nowhere to go: if they leave the Occupied Territories, they become stateless refugees. And if they stay—well, their lives are restricted in ways that are very hard to imagine. Imagine the Covid lockdowns, but for your entire life, generation after generation, and with no vaccine on its way.

(The Israelis have for the most part refused to provide vaccines to the Palestinians under their control.)

Millions of Palestinians are already exiled and forbidden to return. If they stay, they risk being expelled at any time. It’s very hard to see any solution to the problem, since the settlers and the Israeli state are continually expanding, continually creating more and more restrictions. The ethnic cleansing and racial supremacy are marching forward day by day.

This is something that you can understand intellectually. You can wish that the situation could improve. But until you see it, it’s hard to explain how cruel it is, how perverse, how criminal. Because really: who would believe that in this day and age, in a country that likes to call itself a democracy, people are forbidden, because of their race, from walking down the street.

If you’re American, you feel a deep shame. How can you not? We pay for this. Both parties agree with almost lockstep unanimity that we ought to support Israel diplomatically, militarily, and economically, to the point where Israelis have a much higher standard of living than many Americans.

One example: they all have health insurance. Americans, of course, don’t.

And so much of Israel is American. Wonder why career criminal Benjamin Netanyahu speaks English so well? Because he’s from Philadelphia. Maybe-new-prime-minister Naftali Bennett—the one who said “I’ve killed lots of Arabs in my life – and there’s no problem with that”—is from San Francisco. The last two ambassadors to Washington were from, respectively, New Jersey and Miami. A huge proportion of the settlers are American.

The other thing that’s American is the technology. Not just the weapons, which we buy by the billions for Israel, but the technology that we usually think of as fun or harmless. The Israeli occupation is a dystopian nightmare equipped with iPhones and Google and bar codes and scanners. It’s the most modern technology placed at the service of one of the world’s most archaic racial ethnocracies.

And if, on top of being American, you’re Jewish, you feel betrayed. I grew up in the American South. In my family, as in so many other Jewish families, the worst thing you could be was racist. This was a betrayal of both nation and people: of the American promise of equality and democracy, and of the entire Jewish ethical heritage.

I remember how mortified my grandmother was whenever a Jew appeared in the news for something other than winning the Nobel Prize. Of course, there were Jewish crooks, Jewish mobsters, Jewish serial killers, but these people were thought of as the scum of the earth, and were shunned by the respectable elements of the Jewish community. The worst thing you could be was a shanda fir di goyim, a Jew that embarrassed the Jews, and thus justified Gentile persecution and hate.

It’s hard for me to think of the State of Israel as anything but a shanda fir di goyim.

You walk down the street in Hebron. You see people stealing people’s homes because they belong to a different race. And why? In order to build an ugly condo for someone from New Jersey?

And you think: That’s why the six million died?

So what can you do? What can any of us do? It’s the question that keeps me from writing about this subject. Because really: does writing an email on Substack really change anything?

I have to believe that ideas and words still matter. I have to believe that the better parts of human nature can be appealed to.

And there are things that you can do: for example, looking into things like the movement for Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions, the oft-smeared movement to try to force change from abroad. This was the approach the Jewish writer Nadine Gordimer favored toward her own country, South Africa. She had seen how effective it had been in forcing the apartheid regime to stand down, and urged others to use the same approach toward Israel—twenty, thirty years ago, when the occupation was already an international shanda.

But I think that the first thing we can do is break through the rhetorical fog. Recognize that there is an occupier and an occupied, and that the moral duty is to the poor, the powerless, the underdog.

What we can do is withhold our consent.

What we can do is say no.

I welcome comments—

If you want this to keep coming—

And if you like my stuff, please—

Ah Ben -- you've always been our hero & you continue to be so. This is a brilliant, clear-eyed expose of Israeli tyranny and a sensitive painful argument for Palestinian self-determination. Will send to my pro-Israel brother. We miss you & hope to see you very soon. Abby & Helen

Thank you for writing this piece, Benjamin. I started following you for your Clarice Lispector work (and our mutual love of all things Brazil as non-Brazilians!), and admire you all the more for speaking out publicly on Palestine. Much love!