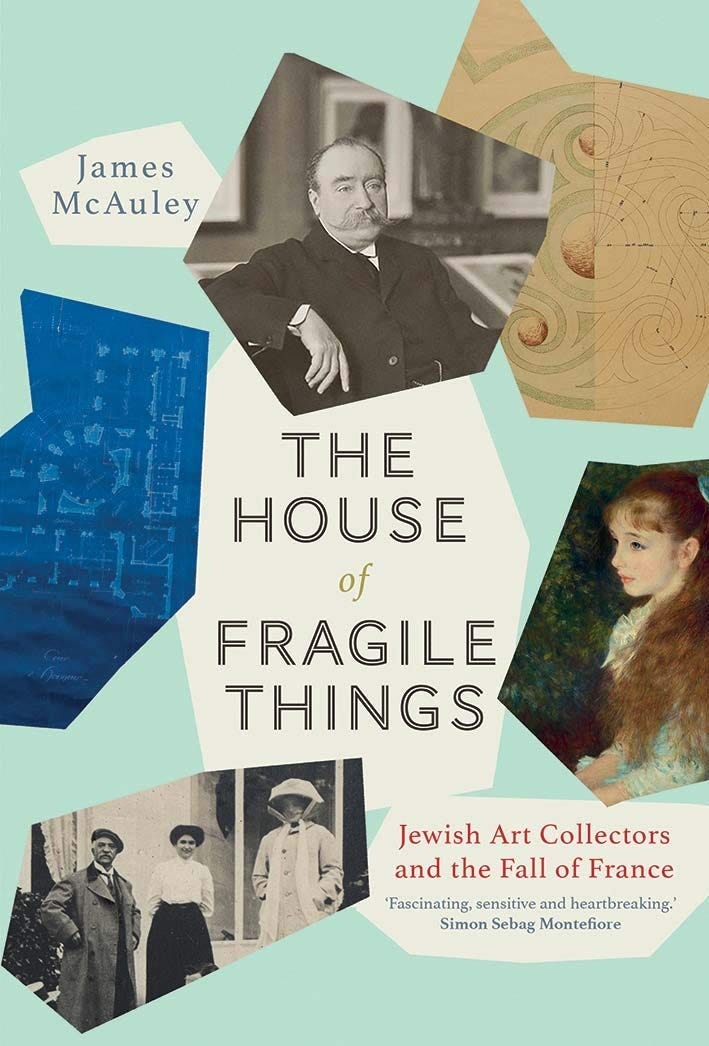

"The House of Fragile Things"

Interview with James McAuley

Is this room in the Musée de Camondo French enough? Spoiler alert: it is not

James McAuley and I go way back. Well, not in terms of time. We’be only known each other for a few years, but we share a background that is only different because he’s from Dallas and I’m from Houston. This means that we share a sensibility.

And what’s a sensibility? Well, this is something I’ve thought about a lot.

In 1964, Susan Sontag published an essay called “Notes on ‘Camp’”. In it, she attempted to define something previously undefined, though she admitted that she was not quite trying to define it. You couldn’t, she knew. You could recognize camp, but it was nearly impossible to pin it down. It wasn’t a thing. It was a sensibility, and a sensibility, like a smell or a taste, could never be conveyed exactly. Moreover, camp was a gay sensibility, hidden from the majority, and took its allure from this hiddenness. That was why she wrote that to define it was to betray it.

I was fascinated by the idea of sensibility. How could you be unable to describe something you could clearly see? How could you tell a straight person’s living room from gay person’s? It was obvious enough; but what were you actually seeing? You had to know the codes. But how were these learned? And how, once you learn them, could you explain them to people who hadn’t? They resided in certain groups, like languages: intelligible inside the community, incomprehensible outside. Inside, you understood. But you would not be able to explain their meaning, as it was not easy to explain a pun to someone who did not speak your language.

A sensibility was a language, and I began to note how many sensibilities I could distinguish. I recognized Jews, and gay people, and Americans; I could spot Brazilians a mile off; and after a few years in the Netherlands, I could tell the Dutch from the Belgians, who in theory are physically indistinguishable, with a hundred percent accuracy. I wasn’t sure what I was seeing. But I knew the difference was glaring.

When I was studying feminist literature, I became intrigued by the differences in how men and women write. Certain French theorists posited that there was a difference, which they called écriture feminine. It had often been discussed in connection with Clarice Lispector. I suspected that there was indeed a difference, but I was never sure what exactly it was, or how it revealed itself. I tried an experiment on some students, asking them to read short texts on neutral subjects, without explicit clues, and then to guess whether the texts were written by men or women. Whether the students themselves were male or female, they could always tell. I asked what gave it away—what they were picking up on—but nobody could say. There was something that they could sense, but they couldn’t say what they were seeing. Later, a photographer told me she always knew when a picture was taken by a woman.

James McAuley and I share the sensibility that comes from a similar background. He’s now written a book, The House of Fragile Things, that is in large part about sensibility—the sensibility of some of the richest Jewish families in France around the turn of the twentieth century, and how that sensibility inspired them to create art collections that were a bid for acceptance as full citizens in a time of raging anti-Semitism.

It answers a fascinating question that I never realized was a question.

Which is: Does this sofa make me look Jewish?

Or: Are Jews allowed to own Marie-Antoinette’s harpsichord?

McAuley discovered how many debates raged around questions like this in the France of the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries. And he shows the heartbreaking fate of three interrelated families—the Rothschilds, the Camondos, and the Reinachs—who created art collections that were intended as gifts to the French nation.

Every Holocaust story is shattering in its own way. But I remember the first time I went to the Musée de Camondo in Paris. It’s a house of an unbelievable opulence and refinement, an absolute dream of Frenchness. It’s so hard to imagine how brutally this perfect world was destroyed; all the Camondo descendants were murdered at Auschwitz just a few years after the patriarch left this monument to the French nation.

McAuley’s book is a study of the sensibility that built this house and others. It’s about how aesthetics and politics can (and always do) clash. And it’s also an extremely moving human story. I asked him a few questions.

One thing that fascinated me about your book is how one particular style of French art became associated with true Frenchness. How did this happen, and why was it threatening for that kind of art to be collected by Jews?

Certain styles from the past are constantly rediscovered for a variety of political and cultural reasons. In the period I look at in the book, mostly the French fin de siècle, the style “rediscovered” was the art of the ancien régime, the style popular just before the French Revolution. These were the halcyon days of the so-called “fête galante,” the nonchalant, whimsical fantasy immortalized in the canvases of Boucher, Fragonard, Vigée-Lebrun, and Watteau. In the late nineteenth-century—following any number of political upheavals in France—this style came to be seen as the apogee of French cultural production, a “delicious decadence.”

Moïse de Camondo’s favorite Vigée-Le Brun

The thing about “rediscoveries” is that they almost always tell us more about the period in which the art is rediscovered than about the art itself. That is absolutely the case in fin-de-siècle France. It’s impossible to separate art from politics, and there was a clear conservatism in the revival of that style, given its monarchical origins. Especially after France’s humiliation in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, the art of the ancien régime came to represent a nostalgic ideal of an imagined past, when France was not a weak and impotent republic, plagued by infighting and corruption. They began to see eighteenth-century art—and especially pieces owned by the kings and queens of France—as symbols of a lost France; reviving that style of decorative arts was a means of reviving a nation.

For some, the prospect of Jews buying these pieces was tantamount to a kind of invasion. Édouard Drumont, the most outspoken antisemite in modern French history, is a prime example of this critique. In La France juive, his infamous 1886 tract against the Jews, he considered many Jewish families as material invaders, unwelcome marauders of France’s cultural patrimony. Consider, for instance, his lines on the Rothschild chateau at Ferrières outside Paris. There’s a line where he laments the sighting of particular object with a very particular provenance: “In the middle, like a trophy, there is the incomparable harpsichord of Marie Antoinette, which is heartbreaking to find in this house of Jews.”

Ferrières, a Rothschild palace later donated to the French state

What do you mean by “an aesthetic of hate”?

By that I mean an antisemitism expressed in the language of objects and things. One of the main arguments I try to make in the book is about the specificity of antisemitism in the French fin de siècle.

The history of antisemitism in Europe is often presented as a kind of teleology of tragedy that culminates, inevitably, with the Holocaust. But what’s interesting is that each chapter is different: this is a hatred that, yes, targets the same people throughout history, but it does so in different terms depending on time and place.

In the fin-de-siècle, the way many Jews were attacked was material and aesthetic in nature. They were targeted with the language of objects and things. One of the main goals of this invective was to depict the Jews as facsimiles of Frenchman who could never know and create true, authentic beauty.

“I was haunted by the idea of the falsehood of the objets d’art that surrounded me, by the falsehood of the painting, by the falsehood of the sculptures, and especially by the falsehood of the gilded bronzes,” wrote Edmond de Goncourt, describing the collection of Edmond de Rothschild, one of the finest collectors of the period. The right-wing writer Léon Daudet said much the same about the collector Gustave Dreyfus, famous for his bronzes.

He decried a ‘bizarre, Oriental piece of furniture, resembling a fence screen from a mosque, reserved as a smoking room” that he saw one night chez Daudet, where many other guests were prominent Jews—Weisweiller, Fould, Ephrussi, and Seligmann, among others.

For Daudet, these men were all ersatz imitations of Frenchmen, each of them ‘truncated, hybrid beings…in search of an impossible nationality.” This was a viciousness that transcended the typical snobbery of aristocrats and tastemakers. Both Jewish collectors and their critics saw in certain objects pieces of a vanished past that carried a powerful potential for projecting an image of national belonging in the present. This was especially true in a moment when the very notion of Frenchness was more fiercely contested than ever before, when the Dreyfus Affair and the antisemitism it unleashed became existential questions for the future of France.

Edouard Drumont was “first and foremost an antiquarian.” Why is this so important?

This underscores the material inspiration for so much of Drumont’s antisemitism. This is the origin of his critique. As an antiquarian, Drumont had an animating nostalgia that soon became an animating violence, as nostalgia often does. He lived in a time when Paris was massively transformed, and he longed for the capital he remembered from his youth, unmarked by railroads and department stores. Eventually he blamed the Jews for what in his eyes were lamentable urban transformations.

“A light went on in my mind,” he wrote in 1892. “I was struck by a terrible power of this race that had, in a few years, trampled on the race of the ancient French.” There it was, the root of his antisemitism, the source of his entire project. For him, the Jewish menace was first and foremost a material menace.

Charles Cahen d’Anvers at the Château des Champs

A lot of the evidence for your figures’ inner lives is missing. How do you see their inner lives reflected in their collections ?

To collect is to create. Collectors do not so much arrange or even possess objects as transform them. What collectors create are themselves. This is what I try and do in the book: I consider the collections essentially as a series of self-portraits. I feel very strongly that, as historical sources, objects and things can often surpass the insights of traditional “texts.” There’s a whole emotional, sensual, tactile dimension to our relationship to objects. As the historian Leora Auslander has written: “People’s relationship to language is not the same as their relation to things.”

Many Jews collected contemporary art. Why did you focus on families known for collecting a specific kind of older art?

What I try and do is to paint a portrait of a beleaguered Jewish elite on the verge of catastrophe, a group of people who were truly at the heart of political, cultural, and intellectual life in the Third Republic. They were members of the French parliament; founders of some of the greatest French banks, some of which survive today; governors of France’s major museums. They were enamored with the French Republic, which had legally emancipated the Jews before anywhere else in Western Europe.

And so they embraced French art, specifically the art of the ancien régime, with a fervent passion, all with an eye to donating their collections to the state when they died. All of them did: each of the families I write about left a major bequest to France, and all are now museums you can still visit today.

While many other Jewish collectors were invested in contemporary art and, in general, in modernism, these collectors had other interests.

On one level, they were responding to anti-Semites. But on another level, they were seeking to write Jews into French history, by showing their love for the finest objets d’art that tradition produced. This was clear in many of their last wills and testaments, but the one that stuck with me the most was that of Moïse de Camondo, who bequeathed his mansion in the rue de Monceau to the French state when he died in 1935. It was named in honor of his son, Nissim, who died fighting for France in the First World War:

By bequeathing to the state my hôtel and the collections it contains, I intend to preserve in its entirety the life’s work to which I have attached myself: the reconstitution of an artistic residence of the eighteenth century. To my mind, this reconstruction must serve the education of artists and craftsmen, and it also allows to be kept in France, gathered in a special environment for this purpose, the most beautiful objects that I could collect from this particular decorative art, which was one of the glories of France during the period I loved most among all others.

Of course, the history of the country Moïse de Camondo thought he understood continued after his death. During the Second World War, his daughter, Béatrice de Camondo, along with her ex-husband and two teenage children, were all deported from France and murdered in Auschwitz.

Béatrice de Camondo

Support Jake! It’s his first book and it’s outstanding. I’m not saying that because we’re friends. I never bother people with bad books because … life is hard enough. Here’s where you can get it.

And if you like this newsletter, support me! It would mean a lot if you’d subscribe.

If you want to leave either of us a comment, just click here.

Two weeks ago I read McAuley's book. Benjamin is right: this is a great and important book!

Fascinating interview - thank you! Impatient for the book . . .