I can’t tell if I miss traveling. Of course, I fantasize. I don’t appreciate being locked in. But it has been wonderful to experience the seasons, which in my life have been … optional.

(Depressed by wintry Amsterdam? Head to sunny Rio!)

I once read that we are the first people in all of history who don’t know the constellations. We’re also the first people in history who can skip seasons. So it’s nice to be where I actually am, rather than always on my way somewhere else. And the fantasy of travel is a pleasure of its own.

In that spirit, here’s something about Finland. I loved Finland. It helped me understand how much of Europe—in fact most of it—is postcolonial. It’s something we don’t associate with Europe. But most of it has in fact been colonized. By other countries or, and sometimes more insidiously, internally.

My awareness of this history is one thing that brought me away from the view that colonialism is a product of racism or imperialism toward a more Marxian class-based view.

A long story. Maybe I’ll tell it sometime soon …

… particularly if you subscribe! This stuff doesn’t, as the saying goes, write itself. And the encouragement and the support mean a lot. As do your comments and emails. Keep ‘em coming! Even if I don’t get a chance to reply (I try) I do read them.

And if you’re already a subscriber but want to give a gift subscription, click here.

For the painter, there are advantages and disadvantages to not knowing what the Sampo looked like. The Kalevala, the Finnish epic, says that it was made with a forge, that it had a lid, and that its loss would bring calamity; and with this scant information Akseli Gallen-Kallela embarked, in 1893, upon The Forging of the Sampo, solving the problem by not showing the mysterious object but the men creating it.

I am looking at them when the lights go out at the Helsinki Ateneum. It is Monday, and in the hushed atmosphere of the closed museum the darkness makes the forge glow. The northern forests from which the Sampo legend emerged are suddenly all around, and it’s a little disappointing when the security man finally shows up to switch back on the lights.

Not knowing what the Sampo looked like was one thing. But the curator who is showing me the museum describes a less obvious challenge: when he unveiled the picture in Paris, the artist failed to emphasize clearly enough that these animal-skin-clad barbarians were mythological. “People thought that this was modern-day Finland,” she says. “That this was how Finns looked.”

Even for my best-traveled acquaintances, Finland’s contours were as vague as the Sampo’s. Almost nobody I knew had a much clearer idea of the place than the Parisians baffled by Gallen-Kallela; and as I got to know Finland, the story of his efforts to show his unknown land—stymied by incomprehension and then, with different packaging, meeting better results—came to seem typically Finnish.

Questions of self-presentation recur in a country invariably ranked among the world’s best, a place so lovely and prosperous, so encouraging to a belief in human perfectibility, that I felt guilty about walking through its capital on the very day a preacher announced the planet would be annihilated in a seismic apocalypse. There are plenty of cities where one suspects the end is nigh: Helsinki is not among them.

Yet cleanliness and prosperity are not, to say the least, the hallmarks of Finnish history. Tacitus wrote that the Fenni “live in a state of amazing savageness and squalid poverty,” and seventeen centuries later an Englishman cringed: “The manners of the people were so revolting that one hesitates in giving the description of anything so disgusting.” When Gallen-Kallela was a boy, fifteen percent of the population starved to death.

Finland’s journey from Sampo to salon was so quick that the country, even today, has not entirely agreed on what, exactly, it ought to be: it is hard to think of another country that has spent as much time in recent years producing detailed reports about its “brand.” (In 2010, after thousands of consultations, the branding commission’s 183-page report, Mission for Finland, settled on “Durable products, clean water, and teachers.”)

The terminology is new, but the idea is not. The commission rightly noted that in Finland “branding started before the country became independent.” They might even have noted that branding is the reason it became independent. The prosperous Western European country we know today is the work of people like Gallen-Kallela in an age when none of those words—“Western,” “European,” and “country”—could safely be applied to Finland.

The early branders faced a nearly empty canvas. “The rich cultural history of Europe has left fewer marks in Finland than anywhere else in the Western world,” a British ambassador wrote in the 1970s, his tone little changed from his compatriot’s two centuries before. The country is remarkably unburdened by ancient monuments: like America’s, its visible history mostly begins in the late eighteenth century.

Helsinki, as a city, is slightly younger than Knoxville, and slightly older than Indianapolis. In 1809, a Polish visitor found “one of the most insignificant and wretched little towns in Finland … rocks and impassable mud [with] no architecture at all. Granite boulders rose between the houses and the streets, while among the houses and the streets next to the customs post there was a putrid swamp that infected the air with its exhalations.”

In that year, Finland, Swedish for seven centuries, was conquered by Russia. For Sweden, the loss of a third of its territory and population was a calamity, and led the Swedes to fall back on their romantic past: “From poetry to art, the Vikings emerged, armed to the teeth, from their tumuli.” Dingy Finland, however, was elevated to the dignity of a Grand Duchy, its laws and liberties guaranteed by the tsar.

As Grand Duke of Finland, he had his own dignity to consider, and that demanded better than the dump to which he moved his government from Turku (“the wretched capital of a barbarous province,” in the words of yet another Englishman). To create a new capital, he gave the architect’s rarest and most coveted commission—the building of an entire city—to Carl Ludvig Engel, a German, who devoted the remainder of his life to the task.

“All of Finland,” Engel wrote his parents in 1816, “is nothing but a rocky cliff … boulders the size of buildings must be blasted away where the new streets will be laid out.” Inspired by St. Petersburg, Engel’s city is less hell-bent on grandiosity; and if it has, by some estimates, the world’s highest quality of life, that is at least partly thanks to Engel’s talent for combining monumentality with the human scale that Petersburg noticeably lacks.

The oldest districts even have an unexpected resort air. Kaivopuisto is a neighborhood of embassies, high upon a rocky promontory, surrounded by marinas and overlooking the islands dotting the bay. This chilly Monte Carlo is a legacy of Helsinki’s brush with the international limelight, in the 1840s, when Russian aristocrats forbidden to squander money abroad came here, to the almost-abroad of the Grand Duchy.

Money was not all they squandered in Kaivopuisto’s casinos—“during a night of bad luck a Count Kushelev gambled away a thousand of his serfs, [and] the general’s wife Krishchanovskaya, who had a famous cook, staked him against a large sum, and lost that dear ‘soul’ of hers”—but before long the political winds shifted and the revelers returned to Baden-Baden and Karlsbad, leaving the new city, once again, in the back of beyond.

Today, it is sad to walk through the splendid capital of the best country in the world and remember other cities—Warsaw, Kiev, Tbilisi—where tsarist rule was less benign, and to imagine how much suffering the world might have been spared if the Romanovs had ruled their whole empire as they did Finland. Engel’s city was not, after all, the only benefit Finland received from Russian rule.

One element of their rule was an attempt to draw the Finns away from their ancient association with Sweden by fostering a Finnish identity, particularly through the use of the Finnish language. Today it feels as normal to hear Finnish in the streets of Helsinki as it does to hear Italian in the streets of Rome, but until the First World War, more Finnish-speakers lived in St. Petersburg than in the capital of Finland.

In the early nineteenth century, when Engel was demolishing giant boulders in the streets of downtown Helsinki, Finnish was a collection of peasant dialects distantly related to Hungarian whose written literature, like that a Native American tribe, was no more than a Bible translation and a handful of religious texts. For all practical purposes, Finland’s literature is roughly as old as California’s.

As throughout much of the previous millennium, the language of culture and government was Swedish, and those who did not speak it—which was most people, especially outside the cities—were condemned to a second-class existence. Over the course of the nineteenth century, Finnish gained a grudging equality; and when Finland became independent, in 1917, it had two national languages.

But Finland’s bilingualism is different from Canada’s, say, or Belgium’s, because Swedish-speaking Finns are so few, only around five percent, though in the national consciousness they loom large. Karoliina Kivijärvi, a television producer in Helsinki, sums up the stereotypes: “That they’re tanned, they sail, they play tennis. They wear Burberry scarves and are a little too interested in royal weddings. That they’re exclusive and keep to themselves.”

The term connected with the Swedish-speaking Finns is bättre folk—“the better people” or “the better sort”—and no phrase as reliably makes their skin crawl. Robert Paul, who directs the Swedish-language health service in Turku, says that “I work every day with alcoholics, abandoned children, the unemployed, and I can tell you that the idea that Swedish-speakers are all rich is simply a lie.”

But for centuries, Swedish made the difference between education and illiteracy, between urban horizons and rural toil, between cultural isolation—the first novel in Finnish was not published until 1870—and contact with the wider world. Swedish showed the Parisians that Finland, dominated by Russia, was Scandinavian and European, and on this subject there was much doubt, even in the twentieth century.

“Young writers: travel to Europe!” a journalist exhorted in 1927, around the same time another succinctly asked: “Finnish—European?” In an age obsessed with race, the Finnish language suggested that the Finns were inferior “Mongoloids,” whereas the Swedes, whatever their other flaws from a Finnish perspective, were at least unquestionably European. Their language lent “Mongoloid” Finland an Aryan veneer.

When the war discredited these racial theories, the Soviets still threatened Finland more directly than any other unoccupied European country, and its efforts to identify as Scandinavian became a matter of survival. This nation-branding was so successful that today no one thinks of Finland as anything other than European, and Swedish is no longer needed for its connection to Scandinavia: as Finns rightly point out, they also speak English in Stockholm.

But these are not the arguments one most often meets. In this egalitarian country, opposition to Swedish contains an aspect of class warfare and racism that has terrified many Swedish speakers to the point of comparing themselves with German Jews. Despite the wild exaggeration, it is remarkable how many of the stereotypes (they’re millionaires who keep to themselves) seem lifted from the lexicon of anti-Semitism.

Opposition to the mandatory teaching of Swedish has been central to nationalist politics, and Paul’s community has often felt besieged. “We talk about it every day at work, about whether there will be any place left for us.” But Kivijärvi has a different idea about what’s behind the term bättre folk. “It sounds like they think they’re better,” she says, “but the problem is our fear that they really are. Finns have a terrible inferiority complex.” In the best country in the world, this anxiety feels like meeting a gorgeous woman convinced she is morbidly obese.

“We want to thank you for bringing us so much joy by having the courage to visit our poor Finland, which can offer nothing but mud roads and fly-infested forests,” the architect Alvar Aalto wrote a Hungarian colleague in 1931. The roads have improved, but the theme, in conversations, often recurs, a reminder that Finland, in many ways, is a post-colonial country, and explaining why the issue of language is as fraught here as in India or Nigeria.

Today, Finland publishes more books, per capita, than any other country in the world, Iceland excepted. But Finnish did not become a literary language until Elias Lönnrot was assigned a post as district health officer in the northern Finnish town of Kajaani, population around 400, in January 1833. It is hard to convey what the words “northern Finnish town” mean, particularly when combined with the words “January 1833.”

Even in the twentieth century, artists came to Finland, and especially to its farthest reaches, as Gauguin went to Tahiti. Finland meant a primitive existence unblemished by the soulless mechanization of the modern city; and in a life that included long sojourns in Kenya and New Mexico, Akseli Gallen-Kallela finally settled closer to home, in a house that, for eight months a year, was accessible only by ski.

You needn’t go far from Helsinki to feel the land’s Patagonian isolation. Just outside the capital the forests and lakes begin, and after a couple of hours, when the divided highway ends, I started to realize that, though I had ticked a destination into my GPS, I wasn’t actually going anywhere: three more days of this—gas stations and vegetation thinning, already endless days lengthening into ever whiter nights—would bring me to the North Cape.

With rare exceptions, the towns north of Helsinki, even the bigger ones, are unimpressive; and the farther north I went—in the summer, in a Volkswagen, on a perfectly paved highway—the more my admiration grew for Lönnrot, whose journeys proved that the Finns, so poor that the government commissioned him to write a work on the use of lichen as an emergency food, were “capable not only of poetry, but of epic.”

In fifteen years of wandering, Lönnrot, “walking, rowing, skiing, and using vehicular transport only occasionally,” traveled a distance equivalent to that from Helsinki to the South Pole. He suffered hunger, vermin, and violence, but the worst enemy was the monstrous loneliness that eventually, in a trip lasting over a year, unleashed a nervous breakdown, only halted by a religious conversion.

His labors were rewarded, however, with the “excitement that palaeontologists felt on discovering a live coelacanth.” Hounded from civilization by Lutheran disapproval, the pagan poetry had scraped by in the darkest corners of Finland and Finnish-speaking Russia, in the great forests where Lönnrot found a dying Homeric universe, a world as remote in time as it was in place.

Illiteracy is essential for preserving epics. Memory contracts as other means of collecting information, particularly writing, proliferate; and the art of men like Arhippa Perttunen, whose performances stretched over days and who provided thousands of lines to Lönnrot, were on the verge of extinction, as Perttunen himself was well aware. His sons, he told Lönnrot, would not know the poetry as he did.

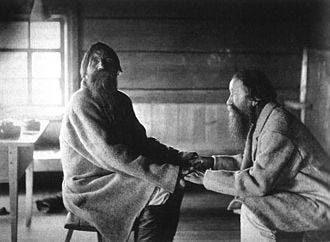

Photographs survive of one those sons, Miihkali. Bearded like a Tolstoyan peasant and blind like Homer himself, he was nearly as great a master as his father, and his magnificently savage appearance suggests why educated urban men like Gallen-Kallela might have been self-conscious about the Parisian belief that Finns looked like his Sampo-forgers: Quite a few, as it turned out, actually did.

Some still do. When I meet him outside Stockmann, the department store in downtown Helsinki, Sami Hinkka, with his long blond hair and beard, looks slightly countercultural, but nowhere near as feral as he appears on stage: as the bassist for the heavy-metal group Ensiferum, he and his bandmates perform topless, in leather pants or kilts, their faces painted in loud colors.

Sami Hinkka (left)

In these outfits, storming the walls of Palermo or evicting starving peasants from a cruel boyar’s estate in Novgorod, Ensiferum could seem terrifying; but Hinkka is a friendly former kindergarten teacher who, on a recent Caribbean cruise called 70000 Tons of Metal, took time between performances to practice yoga. He is also a devotee of Lönnrot’s Kalevala and has used verses from the epic in his own songs.

“Maybe metal is popular in Finland because the same rhythmic structures and keys are found in our folk poetry,” Hinkka says, betraying his classical training; and indeed metal is popular enough to have been inducted into the national “brand”: “Finns should not be shy about highlighting their strangeness,” the corporate visionaries declared in Mission for Finland. “Finns are a dynamic people with their own particular kind of madness.”

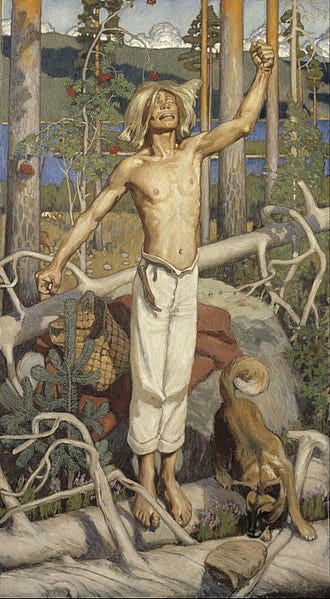

But recreational, middle-class madness—head-banging on a cruise ship, “thinking outside the box”—is not the real madness of “the luckless lands of the North.” That is the madness born of distance and destitution that besieged Lönnrot on his longest journey, and which found expression in the most memorable figure of his epic, Kullervo, whose unrelievedly tragic story forms the emotional climax of the Kalevala.

A magical genius mistreated even before birth, abandoned, enslaved, and tortured, Kullervo’s life includes incest, murderous revenge, and, at the end, a particularly bloody suicide. It is not, to say the least, a Christian story. There is no possibility of salvation or redemption; Kullervo’s defeat is so utter that it is says something about the paucity of authentically Finnish heroes that he could be taken as a patriotic symbol.

At the National Gallery, the curator points out a sculpture based on Gallen-Kallela’s painting of Kullervo. Called the “Statue of Liberty” and erected shortly after Finland’s independence, it is a gracefully muscled nude holding a sword in his right hand and a herdsman’s horn in his left, an Apollonian figure that recalls the sculpture of ancient Greece more than the mad martyr of the Finnish forests.

She points out another image nearby, showing a cowering, emaciated boy: “This is more the way I imagine Kullervo,” she says. But the Apollo was not a coincidence: perched on the very edge of the Western world, the Finns needed to find a way to claim the Western tradition, to give the lie to one historian’s statement that “Without the Mediterranean, its light and its classical foundations, no art was possible.”

An eighteenth-century visitor to the Åland islands was struck by their lack of classical foundations: “I could have fancied myself among the Cyclades […] but here were no temples sacred to Apollo or to Juno; nor had genius and poetry conspired to render every cliff and promontory immortal. Many of the prospects were, however, wondrously picturesque and romantic, and I frequently stopped the boatmen for a minute to gaze upon the extraordinary scene around me.”

Even once Kullervo had been drafted to stand in for Apollo, the question nagged: What was Finland’s classical culture? The only unambiguous answer was the sauna, and in Pispala, a neighborhood of artists on a ridge above Tampere, a city perched between two lakes, I visited the country’s oldest. In this ultramodern country—Tampere is the original home of Nokia—I feared that a sauna here would look like a sauna anywhere.

I needn’t have worried. After bending over a tiny window to pay my fee and hanging my clothes on a wooden spike, I ventured into a tall room with white limestone walls. It was divided, loft-like, into a space below, for showering, and a cubicle on top, for sweating. Men were packed into the unlit upper room, talking to each other and sometimes, incomprehensibly, to me.

A man fat as a sumo wrestler started pouring water onto the rocks. Steam rose in burning clouds. More experienced sauna-goers covered their faces. Afraid to scald my lungs, I struggled to breathe and remain calm, since I was wedged in the farthest corner and could not possibly, in case of an emergency, have made a run for it.

As at an exotic meal where you seem to be the only one shocked by some horrifying anatomical delicacy, the locals chatted away, unperturbed, as the temperature rose; and before I knew it another visitor, not to be outdone, was dumping more water onto the rocks, forcing me to stagger toward the staircase, reaching cooler air just as the steam threatened to separate my skin from my flesh.

Panting in the soft garden breeze, overlooking the idyllic lake and drinking the beer a hostess proffered, I remembered my first night in Africa, when I saw giraffes and a baobab tree beneath a full moon; and my first day in Venice, where I found Gothic palaces teetering into canals. In an age of relentless standardization, it is always satisfying to find that some things are still the way they should be.

Yet there was something slightly 70000 Tons of Metal about its competitive manliness, something out of place in a country that perennially topped international rankings of gender equality. Was the sculptor who transformed Kullervo into Apollo responding to yet another branding challenge, picking him—in a country that had never been independent and had no other macho imagery available—simply because Kullervo was male?

This idea would not have occurred to me if, a couple of days after nearly losing my hide in Tampere, I hadn’t found myself in Turku. Stretching for miles along the shores of the romantically named River Aura, Finland’s oldest city was the “European Capital of Culture” in 2011, and for the occasion a giant building beside the railway tracks was transformed into an exhibition space.

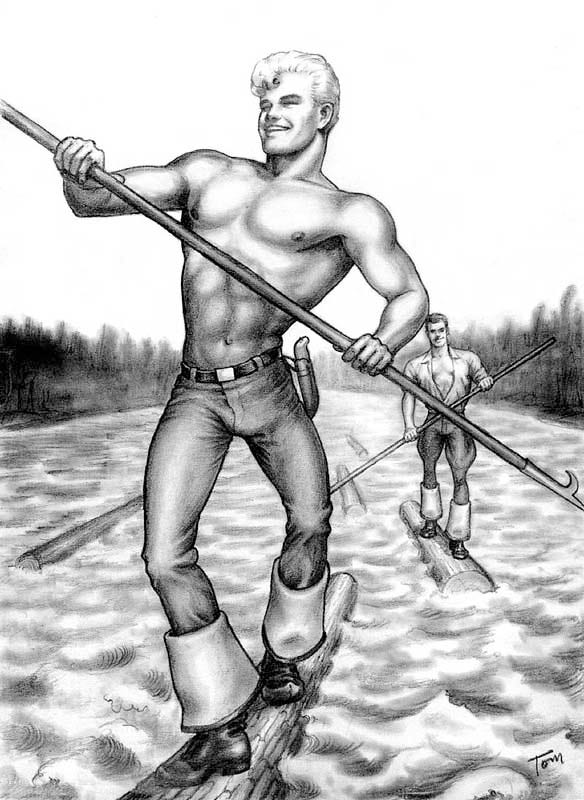

One of them features the most influential artist Turku ever produced, Touko Laaksonen, who, as Tom of Finland, became famous for his images of men with—as Wikipedia delicately puts it—“exaggerated primary and secondary sex traits.” From the fifties on, when his work first appeared in magazines that were still heavily censored almost everywhere, Laaksonen revolutionized the way gay men saw themselves.

Laaksonen’s subjects are extravagantly, hyperbolically masculine, masculine to the point of caricature—a quite deliberate reaction, the exhibition’s organizers explain, to the lisping, effeminate sissies that had earlier defined ideas about homosexuals. Behind their pornographic frolicsomeness, they might as well be shouting the slogan of the African-American Civil Rights Movement: “I am a man!”

As a group of middle-aged ladies is doing their Scandinavian best not to look alarmed (the picture above is one of the tamer ones; I don’t want to get booted off Substack), I wonder what Laaksonen—the muse of artists from Vivienne Westwood to Robert Mapplethorpe to the Village People—would have thought of this posthumous hometown homage. His pictures aren’t usually here, in fact: they have been brought in for the occasion from the Tom of Finland Foundation in Los Angeles.

There, I would have imagined the setting to be an idealized California, but here, suddenly, I realize it can only be Finland: the summery world of lakehouses and cabins and saunas; the Nordic gods whose Viking helmets might be an ironic salute to Finland’s partially Swedish heritage; the hunky lumberjacks like a pervy version of Gallen-Kallela.

But the most Finnish thing about him, I came to think, was Laaksonen’s belief that harsh realities and negative stereotypes could be “rebranded” through words and pictures and art. As I saw how this lonely, despised province had transformed itself into an island of peace and humanity, I thought he might have been right.

What does it mean to be good-looking? What role does attractiveness play in the lives of artists?

Having written two biographies of famously beautiful women, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about these questions. I was mortified (and, let’s face it, flattered) when Cody Kommers, of the Cognitive Revolution podcast, asked what role looks have played in my own life. It’s a serious question, and I was grateful for the chance to talk about it seriously. Your hair is important. Your clothes are important. Your weight is important — and if it’s not, then most of us have wasted a whole lot of our lives, not to mention hundreds of billions of dollars. None of the great women writers, Clarice Lispector, Virginia Woolf, Susan Sontag, Edith Wharton, and so many more, would ever think of these questions as superficial. In so many of their writings, beauty is a matter of life and death. I can’t imagine any gay man—to gay men are often entrusted these arts of presentation—thinking this isn’t important either. If you haven’t heard enough from me this week, give it a listen, and tell me what you think.

I loved reading this. Perhaps we all need a bit of Finlandisation? What about Moomin Troll and Tove? I’d love to see your interpretation of how they fit into the epic tradition and all that.