Dear friends,

Today I got up thinking: I got nothin’.

Try as I might to give the impression that I always have something fascinating to say, that impression is … wrong. And sometimes I get a little bit panicky about this Substack thing — even though one point of it, to me, has been to keep myself to a certain routine. I thought I would write it the way I write a diary or an email, without putting too much pressure on myself. But I’m the sort of person who has a tendency to overdo it. To care too much. Not in that fake-modest way (“My worst flaw is that I’m too generous!”) but to care too much in that hand-wringing way. I spent the last week using Magic Erasers, a product I discovered through my sister, to clean all the markings on the walls of my house. The walls look really good, but the point of this story is that I’m not really someone who needed to become more intense.

The other point of this Substack has been to keep in touch with people I don’t get to talk to or see all the time. This is why I like getting comments and emails. So today I woke up thinking: let the email-writer predominate over the writer-of-fourteen-drafts. This isn’t Macbeth. It’s an email.

As soon as I did that, I felt excitement replace nerves. Because in fact last week and this week I’ve been doing something even more fun than cleaning scuffed surfaces. I’ve been in the Rijksmuseum library in Amsterdam. This is what it looks like:

How do you get to go in here? You make an appointment. You show up. They bring you whatever you want to see. If you want to see the drawings of Rembrandt, for example, you fill in a form on the website a couple of days in advance, sit at a table, and wait for the boxes.

I’m emphasizing the easiness because I am pretty sure that most people have no idea that this is even possible.

When I was doing my research for Sontag in the rare books room at UCLA, a huge print of Venice above my head, I was also teaching a seminar about Latin American literature.

Toward the end of the class, I realized that many of the students, who were mostly graduate students, even knew that the rare books room and the archives were open, welcoming, and full of librarians and archivists who wanted nothing more than to show them their treasures. It was too late in the semester for me to introduce them to these incredible resources. I still regret it.

And it’s the same with museums: before they were tourist attractions with cafés and gift shops selling Vermeer keychains, they were research institutions. They have incredible libraries, collections of prints and drawings and rare books—and there is nothing more interesting that spending a day with them.

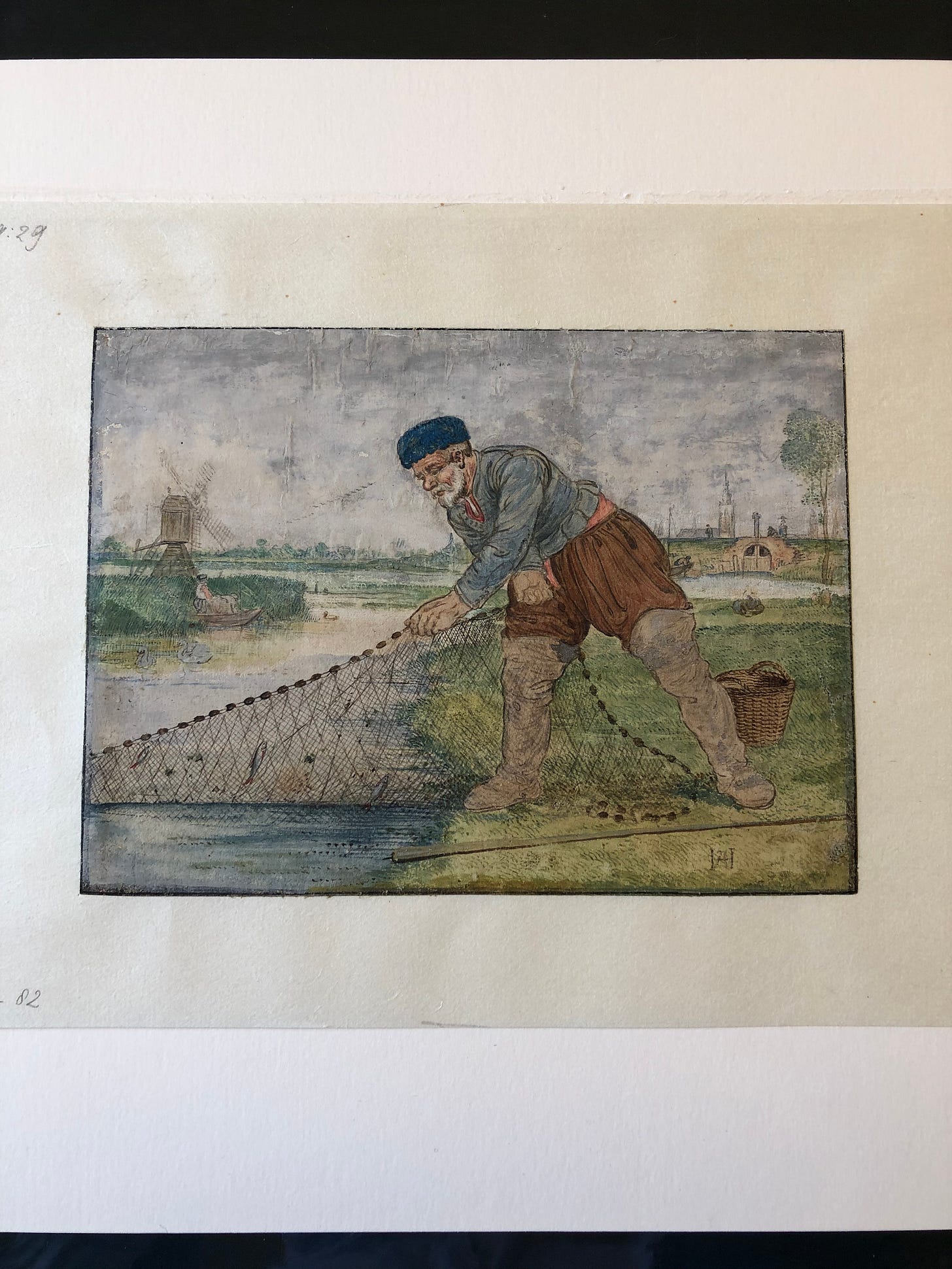

The reason I’ve been there is that I’ve been working on an essay about the 17th-century painter Hendrick Avercamp. You know him, the guy who painted those scenes of fun on the ice.

I’m interested in him for a few reasons.

First, the winters he portrays are utterly gone. The Dutch winter, these days, is a gray drip, drip, drip, nine months long. There aren’t any fat peasants slipping on the ice, or people with ornamental sleighs wearing pointy hats. It’s not even particularly cold. These paintings have become a fantasy for the Dutch as much as they have for everyone else.

Second, Avercamp was deaf, nicknamed “de Stomme van Kampen.” Stomme means dumb, and as in English it means both someone who can’t speak and someone who is stupid. It’s fascinating to learn about how he would have been trained to become such an accomplished artist at a time when there was no such thing as education for the deaf, and only the slightest evidence for sign language, which must have existed in some form. A lot of it seems to have been down to his devoted mother, but as with other figures from so long ago it is hard to know. I’ve been reading a lot about how people with handicaps lived at the time. Then as now, much of it came down to luck, to how involved your parents were, and to what they could afford to offer you.

Third, Avercamp is the subject of one of the craziest books in Dutch art history. If you know anything about Dutch art history, you know this is really saying something. It was written in 1933 by Clara Welcker, the archivist of Kampen, the small city where Avercamp was from.

Welcker is so intrepid as a researcher that she goes back to the thirteenth century to discover the actual location of the field from which the family took its name. (Avercamp means “oat field.”)

Though I know from my own work how addictive research is, how much you regret losing that one document that proves that so-and-so met so-and-so on Thursday—and not, as previously reported, on Wednesday—I kept wondering: Why she is telling me all this? The documentation makes the book especially weird. Because at a certain point I start to suspect: She’s making this shit up. You just know there’s something else going on.

I got a little bit obsessed with this question. I’m an intrepid researcher myself, and I think I figured out what it is. Stay tuned.

What I wanted to show today, though, is something else. Which is just how magical it is to see art in the way you can see it in a place like this, sitting at your table, seeing where the old master touched his pen to the paper. You hold your hand exactly in the position where he must have held it, all these centuries ago.

(It’s an even more incredible sensation now, after the museums and libraries have been closed for so long. Nobody’s around. The weirdest thing about the Rijksmuseum is that the language you hear the most is … Dutch!)

So I wanted to share some of the Avercamp drawings I got to see. Just to show you how wonderful an artist he was. And maybe to inspire you, the next time you have a chance, to delve into the back rooms, and see everything that’s there.

You really get to hold them in your hand.

And zoom in on every detail.

“de Stomme Fecit,” “Made by the mute.” It turns out that the handwriting belongs to no one less than Gerard Ter Borch, one of the greatest of Dutch painters, who lived not far away from Kampen and apparently collected Avercamp’s drawings.

It’s amazing how fresh and bright these drawings are after four hundred years.

Everybody have a great week! And as always, if you’d like to subscribe, do so here:

And if you want to comment:

And if you want to share,

Fascinating read - loved it! Good luck with the magic eraser X

Very funny way to start a piece & it immediately pulled me in to stay for the duration. Anyone who spends days with a wall scrubby & admits it is great. The rest was fascinating but the diary peek into daily you (I've kept a diary since 1974) made my day. Keep scrubbing. Keep researching. I never go into libraries & I'm a writer. Now, you make me want to. I'm heading to Greece in August (I know. I know; hot as New Orleans) & I'm going to find a library (on Kephallonia it might be challenging; likely to be church related) and see what I find.