I woke up in the middle of the night thinking about Anani Dzidzienyo. I knew he’d been sick, and it occurred to me that I hadn’t heard from him in a while. That’s not unusual. Lots of relationships are in deep freeze in the age of Covid, and we don’t see or hear from lots of people. But I knew he had been sick, and as soon as I put his name into Google, the word “obituary” popped up. He died in Providence on October 25.

I last heard from him a little more than a month before, when he sent me a link to a legendarily terrible Portuguese-English phrasebook. (Please do click; it’s amazing.) He mentioned his health problems obliquely, adding: “It is all chato but I am keeping by Kwame Nkrumah’s dictum: Forward Ever.”

That sentence that was typical of Anani. The love of arcana; the admixture of Portuguese; the references to Ghana; the lack of focus on himself.

As I read what I now knew was the last conversation we would ever have, I thought about the first time I ever saw him. (He was the kind of person you always remembered seeing for the first time.) And I thought about how much of my life could be traced to that first meeting.

I have often told how I came to study Portuguese at Brown. I was interested in Asia and wanted to study Chinese, but after a few weeks found myself depressed and drained by the demands of a language that, it seemed, I wouldn’t ever be able to actually learn. So I signed up for Portuguese—and the rest is history.

What I don’t think I’ve ever said is why Portuguese. During orientation, professors from different departments came and talked to groups of incoming freshman. One of these talks featured a sparklingly charismatic African, who talked about how São Paulo, in the seventies, elected a horse to the city council. (I could have the details wrong; something like that.)

This was a man you wanted to hang out with. You wanted to know who he was; you wanted to know the things he knew. Standing on the Main Green in front of Wilson Hall, I talked to him a bit afterwards. I don’t remember about what, but it must have been something about Brazil, because at a certain point, he said: “Ah, but if you want to know about that, you will have to learn the Portuguese.”

I remember the phrase because I remember the “the.” A few weeks later, when I wanted to find a language to replace Chinese, I decided why not the Portuguese. I knew nothing about Portuguese or the world where it was spoken; but one of the great freedoms of Brown was that it let you study whatever you wanted. It let you discover things that were interesting—but that you might not know were interesting.

I signed up for Anani’s own class, “Blacks in Latin America.” I knew nothing about blacks in Latin America. To be honest, I am not even sure I knew that there were blacks in Latin America: as a kid from Texas, my experience of Latin Americans was mainly Mexicans and Central Americans. But taking this class as I was learning Portuguese let a whole new world swim into my ken. This, again, seemed to be the whole point of Brown.

At the time, I was much more interested in Africa than I was in Latin America. And Anani had an encyclopedic knowledge of Africa, starting with his fascinating life story: born in Sekondi-Takoradi, Ghana, he had come on a scholarship from (I believe) the Methodist Church to Williams College in western Massachusetts in the Eisenhower era. I wonder if anyone ever interviewed him, did any kind of oral history with him. The stories of the Gold Coast kid who washed up in Williamstown were hilarious. And though he must have told them ten thousand times, he had the raconteur’s talent of making every time feel like the first time. I hung out with him as much as I possibly could, and read everything he told me to read.

This was … a lot. His knowledge of the bibliography of Africa and Latin America was unbelievable. From Mato Grosso to the Okavango Delta, there was no muddy village, no forgotten bard, no arcane religious skirmish, that he couldn’t recommend a book about. I imagined him as what a great librarian would have been like in the days before computers: someone who knows what’s in every book in the building. I can’t think of anyone in my life who gave me more to read. Somehow I must have understood that Anani wasn’t simply a teacher. He was, if you wanted it, a whole education.

I ended up studying in Brazil mainly because of him. In 1996, when I went to Rio for the first time, it was something like an article of faith among Brazilians that Brazil did not suffer from racism. It had resolved this issue mainly through, well, sex: through creating a mixed-race population in which everyone, to a greater or lesser degree, had African ancestry. This was the big difference between Brazil and the United States, with its “one drop rule” and its view of race as an iron-clad category from which there was no escape, either social or legal.

One thing that makes me feel extremely old is how this stereotype has been flushed down the toilet. Just as he had warned, Brazilians (at least most white Brazilians) really were offended at any discussion of race, a category to which they were utterly blind, and which was only something that Americans brought up because they themselves were obsessed with race.

So you didn’t bring up race in Brazil. It was inviting a conversation that, you knew, was not going to end well — a kind of third rail of Brazilian nationalism — and, well, yes, it was true, of course, that the countries were different. But Anani gave me a key to these differences, to understanding how Brazil worked, that I don’t think I could have found anywhere else.

A generation later, Brazil has changed dramatically, and nowhere more than in its awareness of the ongoing consequences of race and slavery. It’s impossible to trace this intellectual revolution to a single figure, but I wonder if anyone did as much as Anani Dzidzienyo. He was not a writer. This always seemed like a shame to me. He was so funny, so smart, had known everyone and read everything and been everywhere, that I would have read anything he published.

Instead, his legacy is in the truly astonishing number of his students, Americans and Brazilians both, who went on to research and write about the African heritage of Latin America—a subject that, in certain circles, was hardly even considered legitimate twenty-five years ago. Now, as his former students publish book after book after book — and as, year after year after year, his students themselves became professors — that legacy has been enriched with a library so big that even he might have had trouble keeping up.

Another thing occurs to me. Because of Anani, I became keenly interested in his native country, Ghana. And when I graduated from college and came to New York to work in publishing, I was very excited to read a book by a Dutch author about two Ghanaian princes who had been dispatched to the Netherlands in the nineteenth century. It was called The Two Hearts of Kwasi Boachi, and was written by Arthur Japin—who, one day, came into the office to meet my boss. I am sure that some of my enthusiasm for that book came from my desire to know more about the place Anani came from.

(When the book was published in Ghana, we made a couple of trips there— armed, of course, with a huge pile of recommended reading.)

I saw him from time to time over the years. When he was not in Providence, he lived with his wife, Rose-Ann Mitchell, in London Terrace—the very same building in New York where Susan Sontag spent the last years of her life. Because he knew everyone, I shouldn’t have been surprised when he (of course) started regaling me with stories of Annie Leibovitz and Susan fighting in his lobby.

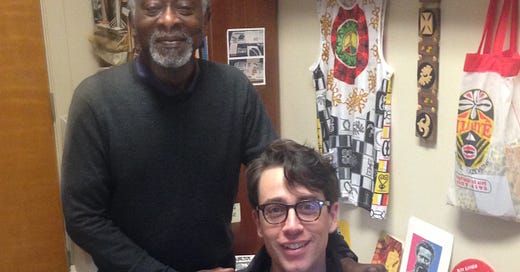

The last time I saw him was in 2016. I was thrilled to take Arthur to Brown, where he had never been. And of course I looked up Anani. We went to his office, where we talked about Ghana, and about how Arthur had helped return the severed head of a 19th century king to a village not far from where Anani was born. Arthur took these pictures of us. It’s too bad you can’t see more of that office. It was a fabulous chaotic collection of everything African and Brazilian. I am so happy to read in this obituary in the Brown Daily Herald that it’s being preserved. It wasn’t an office; it was an artist’s studio.

(Em português: a good obituary in the Folha de S. Paulo describes his contributions to Afro-Brazilian culture.)

This is my first Substack. It’s named for a work by João Guimarães Rosa, simply because the name popped into my mind. Don’t worry if you can’t pronounce it.

I’ve been thinking about a Substack for a while because—

first, my aversion to most social media does not blind me to its good sides, which are keeping in touch with friends and seeing things I would have missed otherwise. I’ve really enjoyed reading other people’s Substacks. It’s a way to keep in touch; and

second, I would like to be able to write things like the above without having to send twenty-five emails to different editors and publications begging for permission and then seeing the piece appear in truncated form six months later when I’ve forgotten all about it. I’d like to be able to write about what’s on my mind, and what’s usually on my mind are people, books, travel, animals, art, politics.

If you’re interested in this, I would deeply appreciate it if you would share it around your own networks. It’s a fact of the pandemic that we are all in need of motivation and encouragement. The more people who are interested in what I’m doing, the more I’ll be interested in doing it.

If you’ve made it this far, thanks so much for reading.

I had a similar experience: woke up last night thinking about him, and just now googled him and the first word was obituary--which led me to your article. Thank you for writing about Anani. I took 2 classes and an independent study with him in the 1990s. He was the best professor and probably the best thing about Brown University.

completely lyrical Ben. Love Substack